I only read two books in January, and I’m a quarter of the way through another.

My first January read was A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles. It tells the story of a Russian aristocrat, Count Rostov, who is sentenced to house arrest by the Bolsheviks in 1922. But his house arrest happens to be inside Moscow’s finest hotel, Hotel Metropol, as he was already resident there when sentenced.

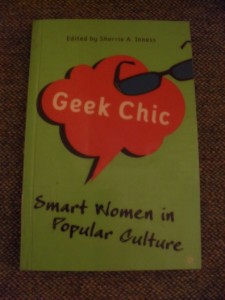

A Gentleman in Moscow (hardback). Published September 6th 2016 by Viking

Over the course of 30 years in the hotel, the Count befriends several of the guests — some come and go while others remain part of the novel’s fabric. The concept of the novel is interesting: the hotel remains static, a stage on which characters enter and leave, but outside the world is changing.

The book begins in the 1920s, shortly after the Russian Revolution, and ends in the 1950s, in the midst of Soviet Russia. Although I was vaguely aware of external events (one character is sent to a gulag prison camp, while Rostov’s friend Mishka writes poetry which is censored), as readers, we are sheltered from all this. The hotel’s warmth and charm is an oasis away from the harsh political climate.

‘Warmth and charm’ sums up the whole book really. Beyond a passing mention here and there, Towles doesn’t elaborate on the brutalities of Russia’s history during the novel’s thirty-year span. It is historical fiction, of a kind, but it’s dressed up in finery and the historical details focus more on luxuries (orchestral music, Swiss Breguet timepieces, fine dining) than gritty reality.

“Does a banquet really need an asparagus server?” one of the characters asks. “Does an orchestra need a bassoon?” Rostov replies.

Although it has been given acclaimed reviews in the media, I thought it was just so-so: entertaining but not outstanding. I enjoyed it as an escapist read and it is well-written, but I’m not sure that it merits all the hype it is getting (rave reviews from NPR, The New York Times and The Washington Post, among others). A review I read on Goodreads classified it as ‘a fairy tale for adults’, which I think is very apt. It’s full of whimsy and charm, but lacks real substance. I’d rate it three stars out of five.

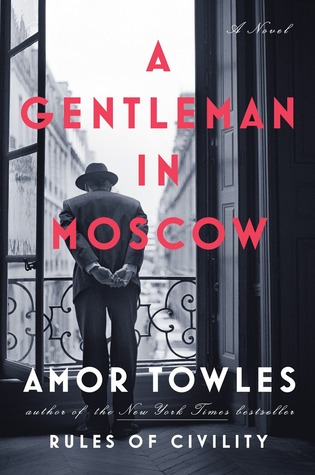

My next book in January was Sweet Caress by William Boyd. In this novel, Amory Clay is the central protagonist. Born in 1908, Amory develops an early interest in photography and aspires to make it her profession, at a time when it wasn’t considered an acceptable career for women.

Sweet Caress (paperback). Published May 17th 2016 by Bloomsbury USA.

Boyd charts Amory’s progress through the early twentieth century as she becomes an intrepid photographer. Her work takes her to pre-war Berlin at first, where she takes secretive photos at an after-hours night club, and later to New York, London and Paris.

She specializes in photojournalism, documenting fascist marches in London, the aftermath of World War II and, later, the conflict in Vietnam. In a stint as a fashion photographer for American Mode, Amory finds that although she is good at it, she is bored by the predictable poses and glossy veneer of fashion photos, preferring instead to shoot photos from a less artificial angle.

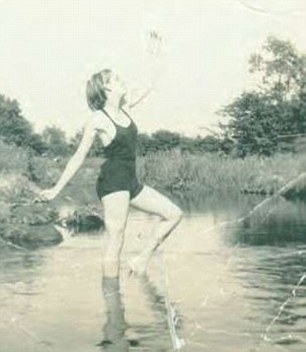

A number of small black-and-white photos are dotted throughout the book, with captions that relate to Amory’s photos. They are anonymous and are all photos that Boyd has found in junk shops and yard sales.

Of course, the photos are all representations of fictional characters, but they make the people in the novel seem more vivid and real. Boyd uses one of these found photos (below) as a frontispiece, depicting Amory as a young woman in the 1920s.

Photo: unknown. Found at a bus stop in Dulwich, London.

The novel is narrated from a first-person perspective, and I really felt that I got to ‘know’ Amory as a character. It’s a mark of an excellent novel when you turn the last page and feel just a little bereft, wishing you could spend more time with its characters.

In the acknowledgements at the end, there is a list of female names: the real-life trailblazing female photographers who inspired Boyd’s depiction of Amory. Sweet Caress left me wanting to research the fascinating lives of these twentieth-century women, most of whom are now unknown.

Currently reading: Where My Heart Used to Beat by Sebastian Faulks.

What did you read in January? It doesn’t just have to be books — if you read a really great article online, share that too!